Widening global horizons

A new research project at the University of Bern is gearing up to challenge notions of European art history by bringing together medieval art historians from across the globe to explore how the representation of space in two-dimensional art works in different cultures.

Author: Faryal Mirza, International Relations Office

Generous funding from the European Research Council (ERC) will enable Professor Beate Fricke to unite international scholars to focus on “Global horizons in pre-modern art”. This marks the first time that a female researcher in the Humanities at the University of Bern has been awarded an ERC Consolidator Grant. This is worth 1.9 million EUR over five years.

Beate Fricke: It will bring together scholars, who work in very different cultural contexts, on how the representation of space in two-dimensional art works in different cultures. Are there mutual changes and developments and can we learn from each other? Could we develop models together to explain phenomena in very distant worlds that deal with similar problems?

Which cultures and regions will you be focusing on?

My collaborators specialize in medieval Japan, Persia, Islam, China, India, Africa and Pre-Columbian art. They are interested in certain objects in Switzerland as Swiss collectors have bought items of tremendous importance but often these are not very well known. These artefacts are normally found in museums of ethnology but often they have not been studied or researched by art historians.

What doors into what worlds are you trying to open in your teaching?

I try to open doors in our minds to understand how globally the world used to be represented and experienced in the past. I try to understand pictures, to make them speak, which is perhaps the most difficult thing I try to teach my students.

Beyond that, I try to teach them openness towards any thought or idea that sparks a new idea by looking at a painting, a constellation of ideas or thoughts or cultures and see how they interact and inspire each other.

Why are you interested in history of art?

Art history is like a time warp - you can travel into the past and discover that images and pictures can tell stories.

I find it fascinating to access the spirit of certain times and individuals that have lived a long time ago, to figure out how they felt, what they found interesting, what has changed since then and how we might learn from that past.

It was a university teacher, whose passion ignited my passion for the subject. That is mostly what studying at university is about: You ignite someone’s passion and get them interested in a topic.

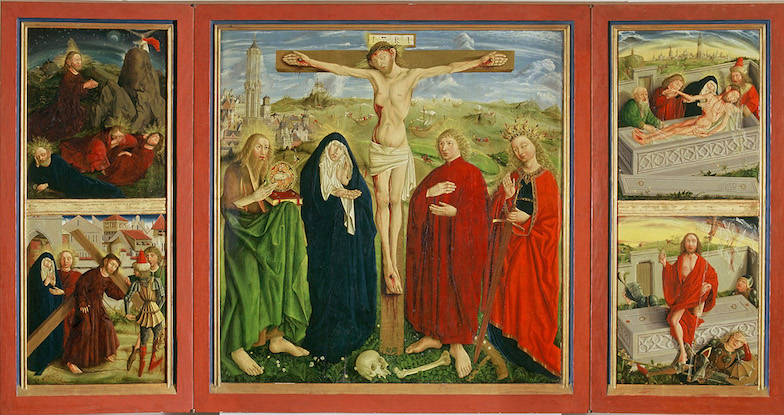

Is there an example of an objet d’art that sticks out in your mind?

The Feldbach altarpiece in Frauenfeld, Switzerland, created in about 1460. We know nothing about this panel, such as who painted it and for whom, and yet I discovered from details on the altar that the painter had read a very specific text that was taught at universities at that time.

This was a text by Johannes de Sacrobosco, a summary of the knowledge, which scholars in the universities of the West were reading in the 13th century. They were digesting knowledge that came from the East, transmitted by Arabic translations of antique texts or commentaries by Arabic scientists. This knowledge revolution was so inspiring and got a huge boost from the university cultures in the 13th century.

How did such cross-border transfers of knowledge take place at that time? The world was a much larger place to navigate compared to the smaller world we know today.

These ideas in the form of written texts in manuscripts and objects like astronomical instruments travelled across borders, countries and languages with scholars, who took notes at universities or made translations of the texts they needed.

That is how these ideas and translations sparked off commentaries, which generated new ideas. These, in turn, sparked scientific innovation in those days.

The project funded by the ERC will also enable a similar cross-border exchange of knowledge to take place.

It will connect scholars, academic contexts and collections of some museums that would not normally be able to connect. It will open the eyes of students and get them in touch with art, which they have never thought about.

My international journey

Find out more about the road travelled by Beate Fricke to get to Bern.

"Global horizons" - ERC grant abstract

“The horizon is the line that seems to separate earth from sky, the line that divides all visible categories into two categories: those that intersect the earth’s surface and those that do not. The horizon is key to the experience of space; it defines our perspective on the visible world. The Global Horizons project will investigate the historical meanings and functions of the horizon in visual and intellectual cultures of the pre-modern world on a global scale. Examining how pre-modern cultures conceived of the horizon opens a crucial line of inquiry into understanding the many different ways in which humans have conceived of the relationship between an invisible cosmos and the visible world.

Non-Western art history is rarely taught at European institutions although countless important works of such art are kept in museum collections all across Europe. Including non-western concepts of pictorial space is key to the project, however, for Eurocentric models of art history have generally privileged the rise of the linear perspective. This framing has limited our understanding of the horizon’s complex rhetorical, visual and epistemological roles.

The project’s specific question connects a variety of objects and epistemological categories, such as panel painting, manuscript illumination, profane und religious objects, cartography, travel accounts, and cosmological treaties. Accordingly, the methodological approaches will range from art history and visual studies to cultural anthropology. Team members will also draw upon interdisciplinary expertise, such as technologies of art production, history of science and philosophy. The project thus makes an important contribution to global art history, a highly innovative area in which only very few pre-modern topics have been addressed. It is the ultimate goal of Global Horizons to suggest a new history of representation in Western medieval art.”